Melissa Cook

From a market on Lagos Island, Nigeria, the skyline of the city of Lagos is visible. Among many companies, there is a great deal of nervousness around investing in Nigeria.

Nigeria has overtaken South Africa as Africa’s largest economy. And with over 200 million people, it is the largest market in the continent, its population nearly twice the size of Ethiopia (110 million) or Egypt (102 million).

Yet among many companies, there is a great deal of nervousness around investing in Nigeria. One business development officer of a large company told me recently: “We’re not in Nigeria; one of our guys heard you can’t go there.”

This kind of second hand hearsay is a risky way to make proper business decisions. When firms make what we refer to as accidental decisions—those based on media reports or anecdotal evidence—it is hard to effectively quantify and manage risks.

Nigeria is definitely a challenging place to operate. But ultimately, the nation is too important to ignore.

Investment by the United States in Nigeria is Growing

Foreign direct investment stock from the United States into Nigeria was $5.8 billion in 2017, up 32.8 percent since 2016, according to the U.S. Trade Representative. However, a significant chunk of U.S. FDI in Nigeria and the continent goes into the resources sector.

The Commercial and Investment Dialogue with the Nigerian government, originally recommended by President Obama’s President’s Advisory Council on Doing Business in Africa, is now in full force, and earlier this year, the U.S. Commercial Service hosted the USA Trade Fair in Lagos, Nigeria—attended by more than 4,000 delegates. Many of America’s biggest firms were out in force, as were smaller names in the agribusiness, aviation, consumer, energy, industrials, and security sectors.

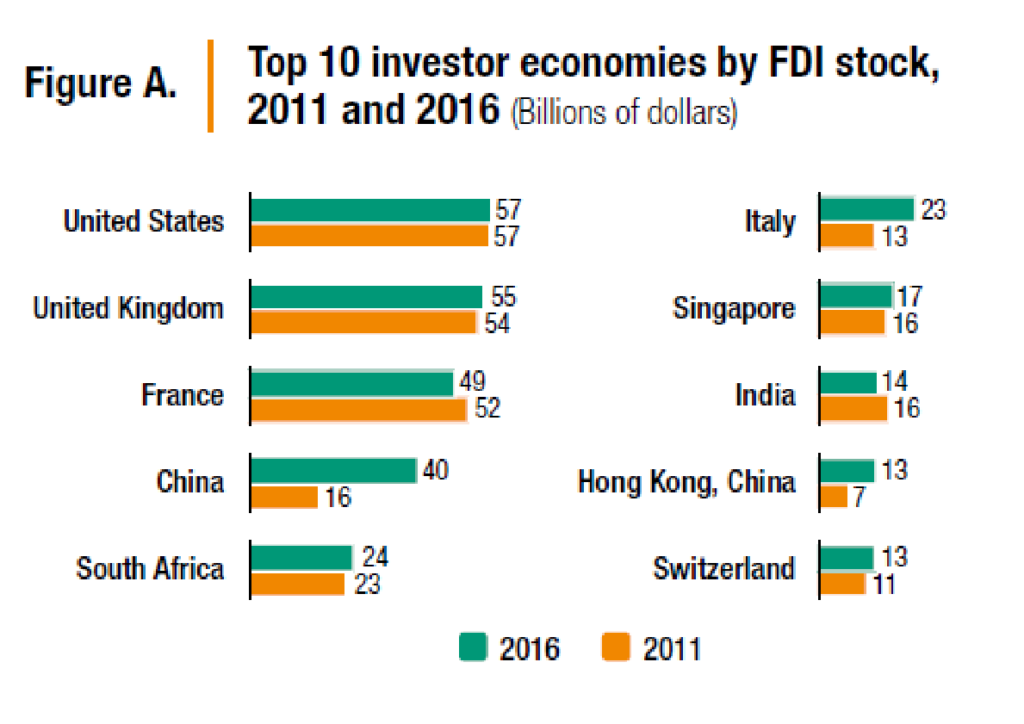

Now, other countries are starting to catch America’s lead—notably the Chinese.

China’s Africa Strategy Presents a Formidable Challenge

China is using all of its political, industrial, and financial might to build deep connections in Africa. Engagement is strategic, multilateral, and well-organized under the biennial Forum on China-Africa Cooperation and the Belt and Road Initiative.

Chinese construction firms are building road, rail, port, communications, mining, and energy projects funded by loans from The Export-Import Bank of China or state-owned banks, using Chinese machinery, and with Chinese operators often operating the asset after completion.

Chinese business development teams visit Africa’s toughest neighborhoods to establish relationships—often long before most American executives have even considered an investment in the country in question. Headlines trumpet Chinese “investment” in Africa, but much of this is actually lending, rather than equity investment. International experience is helping Chinese firms improve their product quality, service delivery, and technological capabilities every day, making them ever-stronger global competitors.

The key to China’s success on the continent is that designing “good enough” equipment for the price their customers will pay. A Chinese-made truck starter will fail after a fraction of the starts a North American truck operator considers normal—but it will also cost a fraction of the price. Likewise, a Chinese-designed smartphone will work on local networks, enjoy long battery life, run the right apps—and come at an affordable price. Despite recent political hiccups, Huawei is the dominant supplier of communications and networking equipment on the continent. Africans benefit from the firm’s low-cost vendor financing, ultra-advanced technology, and turnkey service for modern network installations.

In Nigeria, Demand Exceeds Supply

Nigeria is famous for its power shortages. With only about 5GW of grid power available (on a good day), it’s no surprise that there is an estimated 20GW of captive, backup, and household-level power installed by the private sector.

But this isn’t just a risk. It’s also a business opportunity.

In 2011, Nigeria privatized the power generation and distribution portions of its electricity industry. Performance is well below expectations so far, thanks to gas supply shortages, below-contract tariffs, and poor cash collection. The opportunity? Most manufacturers run their own captive power plants—and they’re investing in advanced gas-fired turbines, high-efficiency production equipment, and renewable energy capacity. Households need prepaid electric meters, energy-efficient appliances, and more cost-effective standby generators.

The continent is becoming a big beneficiary of China’s large-scale investment in renewables—which are now vastly cheaper than they were just a decade ago. In Nigeria, solar, wind, and mini-hydro are rapidly filling in the gaps where grid power is unavailable. Local micro- or mini-grids can deliver power to light homes, charge phones, refrigerate medicines, preserve harvested produce, and bring the internet to schools.

In Nigeria, as elsewhere in Africa, the financial services sector is undergoing a transformation. Mobile money accounts are increasingly popular, led by M-PESA in Kenya. Mobile money has boosted economic activity and brought millions into the financial services sector.

African financial-technology entrepreneurs are testing innovative—and potentially disruptive—services. Where regulations allow, entrepreneurs and mobile operators are introducing low-cost mobile payment, investment, insurance, savings, loans, and cross-border money transfer services using the latest technology.

According to the World Bank, small- and medium-sized enterprises create an estimated 4 of every 5 new jobs in emerging markets, yet traditional corporate banks are still focused on serving large corporate customers.

Can You Create Long-Term Shareholder Value Without Africa?

This isn’t a simple question, but it has to be asked as part of any long-term growth and risk analysis.

Public capital markets are relentless in pushing for short-term earnings and returns. Set aside today’s imperative to meet quarterly earnings expectations, ignore for a minute the potential for activists to disrupt your investment programs because they don’t see an immediate ROI on your long-term strategic investments.

The long-term survival of a business depends on its ability to adapt, grow, and participate in the global economy of the future—and countries like Nigeria are part of this story.

Melissa Cook, is the Founder and Managing Director of African Sunrise Partners LLC

Source: Brink News